I’ve been studying the Neolithic period now for more than 8 years, and I really do think that we can observe shamanic attributes in their way of life, from monument building to daily life. In this post I will explore the Neolithic site of Knowth in Ireland. The aim is to show you how shamanism can be a near-universal framework which can be used successfully to identify the engraved art of the Boyne Valley passage tombs in Ireland – dating to around 5000 years ago – as shamanic interpretations of entoptic visual experience induced by altered states of consciousness.

See ‘What is a shaman’ for an detailed explanation of an altered state of consciousness.

The passage tomb at Knowth, Co.Meath, Ireland

© Ken Williams. Visit his site for more wonderful pictures of Irish rock art here: http://www.shadowsandstone.com

The idea that Neolithic passage tombs were associated with a complex of consciousness-altering traditions, linked to the practice of shamanism took off when David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson proposed that many of the abstract marks found in prehistoric art are entoptic and can be put down to neuropsychological processes, as determined by shamanistic practices. Entoptic phenomena derives from the central nervous system – which are visual effects whose source is within the eye itself. You can see them by rubbing a finger against the eyelid of a closed eye.

Lewis-Williams and Dowson’s entoptic model is based on a huge corpus of work. Even though there are several entoptic shapes, certain forms occur time and time again. Listed below are six of the most common shapes, which were originally derived from work done by neurologists and psychologists. These are:

(a) a basic grid and its development in a lattice and expanding hexagonal pattern;

(b) sets of parallel lines;

(c) dots and short flecks;

(d) zigzag lines crossing the field of vision;

(e) nested catenary curves;

(f) filigrees or thin meandering lines.

It was Lewis-Williams and Dowson who first introduced the entoptic neuropsychological model to explain the art motifs of the Upper Palaeolithic areas of Southern Africa and the Californian Great Basin. One clear positive factor in their model is the certainty that the human nervous system and its capacity to produce entoptic visual imagery in prehistory is the same as today, and so it is said to be universal. These studies were soon followed by Richard Bradley’s, who incorporated motifs from Neolithic Ireland, Brittany and Iberia.

The neuropsychological model, however, did not resist opposition. It was soon criticised by many scholars for having some basic methodological flaws and for not sticking to fundamental scientific principles. Jeremy Dronfield especially, set out to resolve these problems, and added an extra control component to the model: samples of non-entoptic art. He produced an analytical model, which included studies of art which do not occur in an altered state of consciousness. By using his model, it was found – with approximately 80% confidence – that Irish passage tomb art is fundamentally similar to, as opposed to merely resembling arts derived from entoptic phenomena.

Some of the most convincing possibilities of engraved entoptic phenomena and shamanic practice in the Neolithic concern passage tombs. This class of Neolithic monument was constructed across the west and north of the British Isles. Well-known examples include Newgrange and Knowth in Ireland, but there are many others, including for instance Bryn Celli Ddu and Barclodiad-y-Gawres in north Wales. Their layout can be diverse, yet all possess a narrow and restricted passage that leads from the outside world to an internal chamber. In many instances, it was here that the remains of the dead were placed.

The tombs themselves may have acted as receptacles for the veneration of ancestral human remains, although they may have been used for more than just burial. Passage tombs may be understood as settings for rituals which involved the living and the dead – perhaps a centre for shamanic acts – a place where alternative dimensions could be experienced and where communication between the living and the dead could take place.

Entoptic shapes at Knowth

The main tomb of Knowth Site 1 were constructed between 3295 and 2925 cal. BC, and is associated with at least 18 smaller passage tombs. It has the largest concentration of megalithic art in Europe, with more than 300 decorated stones. Within the main mound are two passage tombs, one opening from the east side of the mound and the other from the west.

The main tomb measures 80m by 95m, with the kerb and interiors containing an abnormally large quantity of engraved abstract art. More than a quarter of Europe’s megalithic art and about 45% of Ireland’s passage tomb art is found at Knowth, with Site 1 accounting for about 83% of the total. I will only focus on the engraved art at Site 1, which has 197 stones in total. The entoptic shapes occurring on the stones are illustrated here:

1. The meander shape (entoptic 1) is engraved on kerbstone K83;

2. The arc-spiral shape (entoptic 3) is shown on kerbstone K56;

3. An example of the loop arc (entoptic 5) is represented on kerbstone K68;

4. A clear case of the multiple spiral (entoptic 6) is engraved on kerbstone K13.

Entoptic shapes at Knowth. 1. Entoptic 1 on K83; 2. Entoptic 3 on K56; 3. Entoptic 5 on K68; 4. Entoptic 6 on K13. © Ffion Reynolds

What objects suggest a shamanic interpretation?

Along with the engraved art there are several objects and materials at Knowth that may suggest a shamanic worldview. The first is the use of quartz. Quartz and shamans are inextricably linked, with quartz being used across the globe as an animistic material. I’ve written a paper on quartz at the neighbouring passage tomb of Newgrange, Co. Meath, Ireland. You can view the article here: Quartz as an animistic material at Newgrange passage tomb. Quartz can be seen as a apron or floor around Knowth, and as I argue in the paper, this could have been a very powerful and visual experience for Neolithic inhabitants, especially when you consider quartz’s triboluminescant qualities (when quartz is rubbed together it creates a bright, lightning-like flash of light known as triboluminesence).

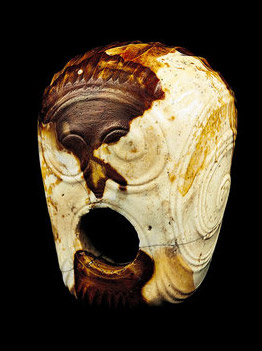

There as several objects which I could discuss here, but one of the most iconic is the Knowth mace-head.

This object was found in the right hand recess of the eastern chamber tomb at Knowth, and it is arguably one of the most skilled pieces of artwork surviving from the Neolithic in Europe. A wooden rod would have originally been inserted into the hole. The picture gives a true picture of its size, at around 80mm in length.

The first clue that this mace-head may have been the possession of a shaman is the decoration. On the sides spirals are engraved, echoing my previous descriptions of entoptic phenomena. The second clue comes from its form. When someone thinks about the practical function of a mace-head – violence comes to mind, although I highly doubt that it was actually used for violence as no marks have been found on its surface – it is in perfect condition.

An alternative suggestion may be that is was a commanding object used to display authority and power. It may be that at this time the possession of awe-inspiring objects like this one, was used in relation to secret knowledge that could be used to predict the seasons and astrological changes – a common shamanic attribute.

I’ll turn next week to the Bronze Age, and explore a fascinating burial and a range of objects that have been considered the property of a shaman since the 60s…

Ffion Reynolds

I used to work at Knowth. It is a wonderful site with a great energy. I can definitely see it being used for shamanic rituals.

I’m currently writing a paper on the rock art at Knowth – could you please share with me some of your resources for this analysis? I would love to be able to explore this side of things further.

Hi Cassie, let me know your email address and I can send you another article I wrote in a book which includes references, Ffion

do you have a source for the non-entoptic samples of Jeremy Dronfield? currently doing my dissertation on lewis-williams model on upper palaeolithic art! 🙂

Hi Sam, Dronfield has written several articles in journals like Antiquity, Cambridge Journal of Archaeology and also the Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Thanks, Ffion

Dronfield, J. 1994. Subjective vision and the source of Irish megalithic art in Antiquity 69.

Dronfield, J. 1995. Migraine, light and hallucinogens: the neuro-cognitive basis of Irish megalithic art. Oxford journal of archaeology, 14.

Dronfield, J. 1996. Entering alternative realities: cognition art and architecture in Irish passage tombs. Cambridge journal of archaeology, 6.

what a shame the link to the paper on Quartz at Newgrange is no longer active…I would really like to read it.

Hi Kevin, check out my academia page for access to the article on quartz: https://www.academia.edu/8611054/Regenerating_Substances_Quartz_as_an_animistic_agent

fascinating, I suppose it’s perfectly natural that the aesthetic becomes imbued with other facets especially if remarkable properties are observed. As a cyclist who has followed past migrations of folk and trade routes, I have frequently stopped to pick up quartz all over Europe. Nice to know that innate affinity may hark back millennia. Thank you.

👍